As India concludes the world’s largest election on June 5, 2024, with over 640 million votes counted, observers will be able to assess how different parties and factions used artificial intelligence technology and what lessons it may hold for the world.

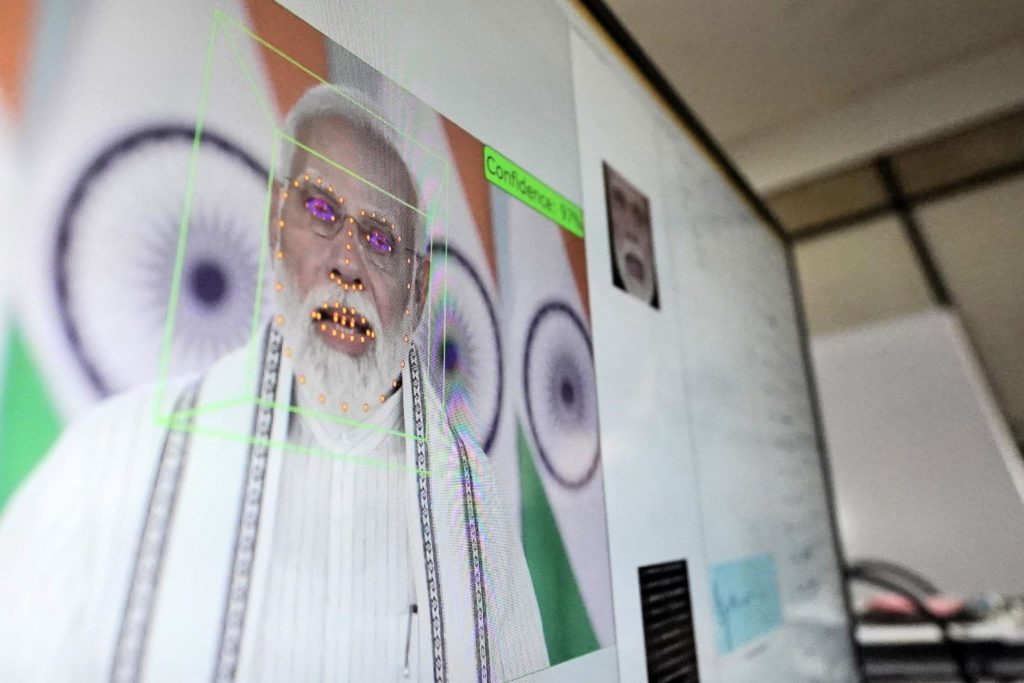

The election campaign made extensive use of AI, including deepfake impersonations of candidates, celebrities and deceased politicians, and by one estimate millions of Indian voters were exposed to the deepfakes.

But despite concerns about the spread of disinformation, most campaigns, candidates, and activists used AI constructively during the election: They used it for typical political activities, including name-calling, but primarily to better connect with voters.

Deepfakes without deception

Indian political parties spent an estimated $50 million on licensed AI-generated content for targeted communication with voters during this election, and it was largely successful.

read more: The FCC is considering restricting AI-generated political ads on TV and radio, but not on streaming.

Indian political strategists have long recognized the impact personality and emotion have on voters and have begun to use AI to enhance their messaging. Emerging AI companies such as The Indian Deepfaker, which started out serving the entertainment industry, quickly responded to the growing demand for AI-generated campaign materials.

In January, Muthuvel Karunanidhi, who served as chief minister of the southern state of Tamil Nadu for two decades, appeared by video at a meeting of the party’s youth wing, wearing his trademark yellow scarf, white shirt and sunglasses, his head cocked slightly to the side in his usual pose. But Karunanidhi, who died in 2018, has endorsed deepfakes.

Deepfake technology has allowed a deceased politician to appear in an Indian election campaign.

In February, the official X account of the All India Anna Dravida Progressive Alliance Party was Audio Clip Jayaram Jayalalithaa, an iconic superstar in Tamil politics, popularly referred to as “Amma” or “Mother”, passed away in 2016.

Meanwhile, voters received calls from their local representatives to discuss local issues, but the representative on the other end of the line was masquerading as an AI. BJP activists like Shakti Singh Rathore frequent AI startups to send personalized videos to specific voters about the government benefits they have received and encourage them to vote on WhatsApp.

Multilingual Boost

Deepfakes aren’t the only AI at work in India’s elections. Long before the polls began, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed a packed crowd to celebrate the connection between the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the city of Varanasi in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. He instructed the audience to put on earphones and proudly announced the introduction of “new AI technology” as his Hindi speech was translated into Tamil in real time.

clock: Tech companies announce rapid AI advances, sparking surprise and concern

In a country with 22 official languages and about 780 unofficial recorded languages, the BJP has adopted AI tools to convey Modi’s personality to voters in areas where Hindi is not easily understood. Since 2022, Modi and the BJP have been using Bhashini, an AI-powered tool built into the NaMo mobile app, to translate Modi’s speeches with narration in Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Odia, Bengali, Marathi and Punjabi.

As part of the demo, some AI companies distributed their own audio versions of PM Modi’s popular monthly radio show “Mann Ki Baat” (roughly translated as “From the Heart”) in regional languages.

Adversarial Use

Indian political parties have doubled down on online trolling, using AI to bolster their ongoing meme wars. At the start of the election season, the Indian National Congress released a short video to its 6 million followers on Instagram featuring the title track from a new Hindi music album, “Chor” (Thief). The video grafted a digital likeness of Modi onto the lead singer and replicated his voice with rewritten lyrics that criticized his close ties with Indian business tycoons.

The BJP retaliated with its own video on its Instagram account, which has 7 million followers, mixing a supercut of Modi campaigning on the streets with footage of his supporters and setting it to its own music: an old patriotic Hindi song sung by Mahendra Kapoor, the famous singer who died in 2008 but has been resurrected by an AI voice clone.

Prime Minister Modi himself tweeted an AI-created video of himself dancing (a common meme featuring rapper Lil Yachty on stage), commenting, “Really glad to see this kind of creativity at the peak of voting season.”

In some cases, the violent rhetoric in Modi’s campaign that endangered Muslims and incited violence was delivered using generative AI tools, but the harm can be traced back to the hateful rhetoric itself, not necessarily the AI tools used to spread it.

The Indian experience

India has been an early adopter of AI, and its AI experiments serve as an example of what the rest of the world can expect in future elections. AI technology can create deep fakes of anyone’s face without their consent, making it harder to distinguish truth from fiction, but its consensual use is likely to make democracy more accessible.

read more: The United Nations has passed a resolution supporting efforts to ensure artificial intelligence is “safe, secure and trustworthy.”

The adoption of AI in Indian elections, which started off with entertainment, political meme wars, emotional appeals to people, reviving politicians and persuading voters through personal calls, has paved the way for AI’s role in participatory democracy.

The BJP’s surprising electoral result, in which it failed to secure the expected parliamentary majority, and India’s return to a highly competitive political system, particularly highlights the potential for AI to play a positive role in deliberative democracy and representative governance.

Lessons for the world’s democracies

In a democratic society, the goal of political parties and candidates is to have more targeted reach with voters. The Indian elections saw a unique attempt to use AI to enable more personalized communication among a linguistically and ethnically diverse electorate, particularly to better reach out to lower-income groups in rural areas.

With AI and the future of participatory democracy, voter communication will not just be personalized but conversational, allowing voters to share their demands and experiences directly with their representatives, quickly and at scale.

India is an example of how this recent fluency in AI-powered inter-party communication can be extended beyond politics: the government is already using these platforms to provide government services to citizens in their own language.

If used safely and ethically, this technology could usher in a new era of representative governance, particularly in bringing the needs and experiences of local people to parliament.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.