image source, Getty Images

Booing your own national anthem – Hong Kong and the dilemma

- author, John Duerden

- role, bbc sports

On January 1, Hong Kong defeated China in a soccer match for the first time in nearly 30 years.

In fact, the official result of the pre-Asian Cup warm-up match was Hong Kong, China 2-1 China.

Hong Kong’s team name will change in 2023, leading to speculation that the days of independent football in the former British colony are numbered as Beijing tightens its grip on the territory.

“At some stage in the future, the Hong Kong Football Association [HKFA] It will no longer exist as an independent member of FIFA,” Mark Sutcliffe, HKFA president from 2012 to 2018, told BBC Sport.

“It’s only a matter of time.”

Hong Kong’s recent victory over China is not the greatest.

It was May 1985, when a 2-1 victory in World Cup qualifying shocked the 80,000 fans at the Beijing Workers’ Stadium.

“Every soccer fan in Hong Kong knows that, even though many of us weren’t even born then,” says local fan Kay Leung.

“It was one of the best nights in our history.”

The defeat is not remembered very fondly in China, as it sparked riots and led to the resignation of the head coach and the president of the Chinese Football Association.

Before the game, Hong Kong, then a British colony, sang “God Save the Queen” as its national anthem.

Things changed in 1997 when Britain transferred control to China. As part of the agreement, China pledged to maintain Hong Kong’s relative freedom under the “one country, two systems” principle and its status as a “special administrative region” for the next 50 years.

Meanwhile, soccer has become a stage where Hong Kong’s liberal democratic history and the mainland’s authoritarian traditions collide.

As the Chinese government tightens its grip, Hong Kong games have become one of the few ways locals can express their emotions.

“For many people, soccer was the natural choice,” Leon says. “It’s more important than other sports.”

The importance of football became clear after the 2014 Umbrella Movement. The movement was named after a series of pro-democracy protests in the financial capital during which protesters used umbrellas to protect themselves from police tear gas and pepper spray. .

The protests were sparked by the Chinese government’s decision to only allow pre-approved candidates to participate in Hong Kong’s 2017 elections.

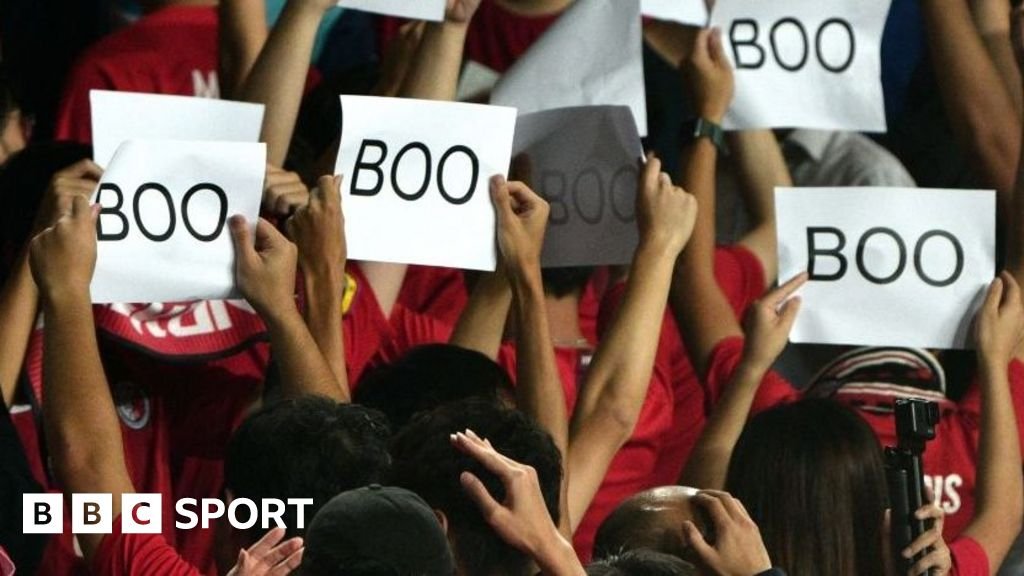

In 2015, Hong Kong hosted China in the 2018 World Cup qualifiers, with some home fans booing their country’s national anthem, which is now shared with their opponents and dubbed the “Volunteer March.”

Some held placards that read “Hong Kong is not China.” The local association was fined by FIFA.

Mr Sutcliffe felt not everyone in attendance was a football fan.

“Without a doubt, the international matches provided a platform for Hong Kong residents to air their grievances,” Sutcliffe said.

“The booing during the national anthem was a huge advertisement for them. Attendance increased and a lot of people who would never go to a football game under normal circumstances went to the game.”

Mr Sutcliffe cannot recall any complaints from Beijing.

“We were certainly under pressure from the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.” [Special Administrative Region] “I want the government to do everything in its power to stop that,” he says.

“We ran a publicity campaign. We introduced stricter security at matches, including searches and the confiscation of banners. We were unable to completely stop it, and as a result we were fined several times by FIFA. I got it.”

In 2020, Hong Kong’s legislature also took action, passing a bill that would make disrespecting the national anthem a crime, punishable by up to three years in prison.

Still, at the first home game open to the public since the new law was introduced in September 2022, the national anthem was once again booed by some in the crowd before kickoff against Myanmar.

Three months later, Hong Kong’s 83 sports organizations were told they had to add “China” to their names or risk losing funding. About three-quarters had never done so before.

Football fans flocked to buy the last batch of shirts that still had the old Hong Kong logo before the word “China” was added to the dragon emblem.

Sutcliffe sought to strike the right balance between accommodating China’s demands while maintaining a degree of distance and independent identity.

“It was kind of an unspoken rule to not get too close in case FIFA decided to disqualify individual members,” he says.

“There was no sharing of resources or knowledge or anything like that.

“In fact, we had a much closer relationship with Japan, who were much more altruistic and saw their role as coaching their smaller affiliates and improving football across Asia. I was thinking.”

The Chinese Super League (CSL) boom briefly threatened to recalibrate these relationships.

In the early 2010s, China’s top clubs started spending huge amounts of money on world-famous players such as Nicolas Anelka, Didier Drogba, Hulk and Carlos Tevez, as well as Marcello Lippi, Luiz Felipe Scolari, Fabio… Coaches such as Capello were also appointed.

The number of participants has increased to the highest in Asia, and standards have improved. Guangzhou Evergrande, just an hour away from Hong Kong by high-speed train, became China’s first Asian Champions League winner in 2013 and won it again in 2015.

In Hong Kong, the possibility of sending a team to CSL has been floated in hopes of improving standards and revenues.

In the end, the boom didn’t last. Financial problems in Chinese soccer, exacerbated by the global pandemic, have resulted in many clubs suspending their activities.

The current leadership of the Hong Kong Football Federation did not respond to requests for a press conference, but they still see China as an opportunity.

HKFA Vice-President Eric Fok Caixiang said in 2023: “We believe that is the direction we are heading.” “Everyone is looking at the Chinese market. When it comes to football, we want to be sustainable in a way that creates commercial value.”

“There are many examples of teams based in one place and playing in another league. Welsh clubs Cardiff City, Swansea City and Wrexham are all part of the English pyramid.”

National team manager Jorn Andersen also welcomed the possibility of Hong Kong’s best clubs playing against teams from China.

Under the Norwegian coach, Hong Kong qualified for January’s Asian Cup for the first time since 1968, but finished bottom of a group that included Iran, the United Arab Emirates and Palestine. China’s performance was not as good, finishing third in the group and failing to score at the first hurdle.

Longtime Chinese fans were impressed by Hong Kong’s effort.

Tobias Szuzer, academic and co-editor of Sports in Hong Kong: Culture, Identity, Policy, said: “On social media, mainlanders are praising Hong Kong’s recent successes and encouraging fan mobilization in Qatar.” It was even praised.”

“Some even think the Chinese team can learn from Hong Kong.”

The dilemma remains for the Hong Kong Football Federation. If the Hong Kong Football Federation is to remain a separate organization with separate teams, it will have to be useful to the Chinese government.

Voting within the Asian Football Confederation and FIFA is one point in the company’s favor. However, its existence is inconsistent with China’s centralized control system.

In February, around 40,000 people bought tickets to watch the match between Inter Miami and Hong Kong League Selection Eleven. Spectators clamored for refunds as star player Lionel Messi remained on Inter Miami’s bench after suffering a hamstring strain, after Inter Miami owner and former Chinese Super League ambassador Heckled David Beckham’s post-match speech.

“Politically, Beijing basically views Hong Kong as part of the mainland,” said Simon Chadwick, a professor of sports and geopolitical economics at France’s Schema Business School.

“If there were a controversy like the recent Messi episode, China would definitely want to avoid losing face and would try to suppress the occurrence of such issues.

“If Hong Kong football is to survive, it would be wise to depoliticize itself and establish a set of values that are seen as pro-social and non-threatening.

“At best, Hong Kong football can look forward to a future of neutrality. At worst, it could become subsumed into mainland structures and governance and face extinction.”

Zuzer doesn’t believe that Hong Kong becoming China’s Hong Kong means major changes are imminent.

“Hong Kong has been participating in the Olympics as Hong Kong, China, since 1997, so recent changes across other national sports associations are rather symbolic rationalization acts,” he says.

“How people support their teams or think about their teams doesn’t really change much.”

But Mr Sutcliffe believes the writing may be on the wall for the addition of one word.

“The name change didn’t surprise me at all,” he says.

“It embodies what I was saying, that it’s just a matter of time. This is part of the transition to assimilation.”