Gossippers, talkatives, meddlers, whatever you want to call them, gossips get a bad rap. But a new theoretical study conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland and Stanford University argues that gossipers (defined as people who exchange personal information about absent third parties) aren’t all that bad. There is. In fact, they may even increase the level of cooperation within your social circle.

The study was published on Tuesday Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used computer simulations of social interactions to show that gossip is good at disseminating actionable information about people’s reputations.

Study co-author Dana Now said, “When you want to know if someone is a good person to interact with, if you can get that information from gossip (assuming that information is honest); It could be very beneficial.” He is a retired Professor of Computer Science and Systems Research at UMD.

Researchers used computer simulations to explore a long-standing mystery in social psychology. “How did gossip evolve into a pastime that transcends gender, age, culture, and socio-economic background?”

“One previous study found that people spend an average of one hour a day talking about other people, which means they take a lot of time out of their daily lives.” said lead author Dr. Xinyue Pan MS ’21. ’23 published part of this research in his master’s thesis in psychology. “That’s why it’s important to learn it.”

Previous theories have suggested that gossip can bond large groups of people and encourage cooperation, but it remains unclear what individual gossipers gain from these interactions, and It was not explained why recipients of gossip were willing to listen.

“This was a real mystery,” said study co-author Michele Gelfand, a professor at Stanford Business School and professor emeritus of psychology at UMD. “It’s unclear why gossip, which requires considerable time and energy, evolved as an adaptive strategy in the first place.”

To better understand the complex web of gossip, the research team used an evolutionary game theory model that mimics human decision-making to understand how agents, or virtual research subjects, interact and receive rewards. Observe how you change your strategy to receive.

In this case, the researchers wanted to find out whether agents use gossip to protect themselves or to exploit others. Agents may cooperate with or betray the gossiper. They can become gossips themselves. And they can change their strategies after observing the outcomes and rewards of other agents’ decisions. By the end of the simulation, 90% of the agents’ girlfriends were gossipers.

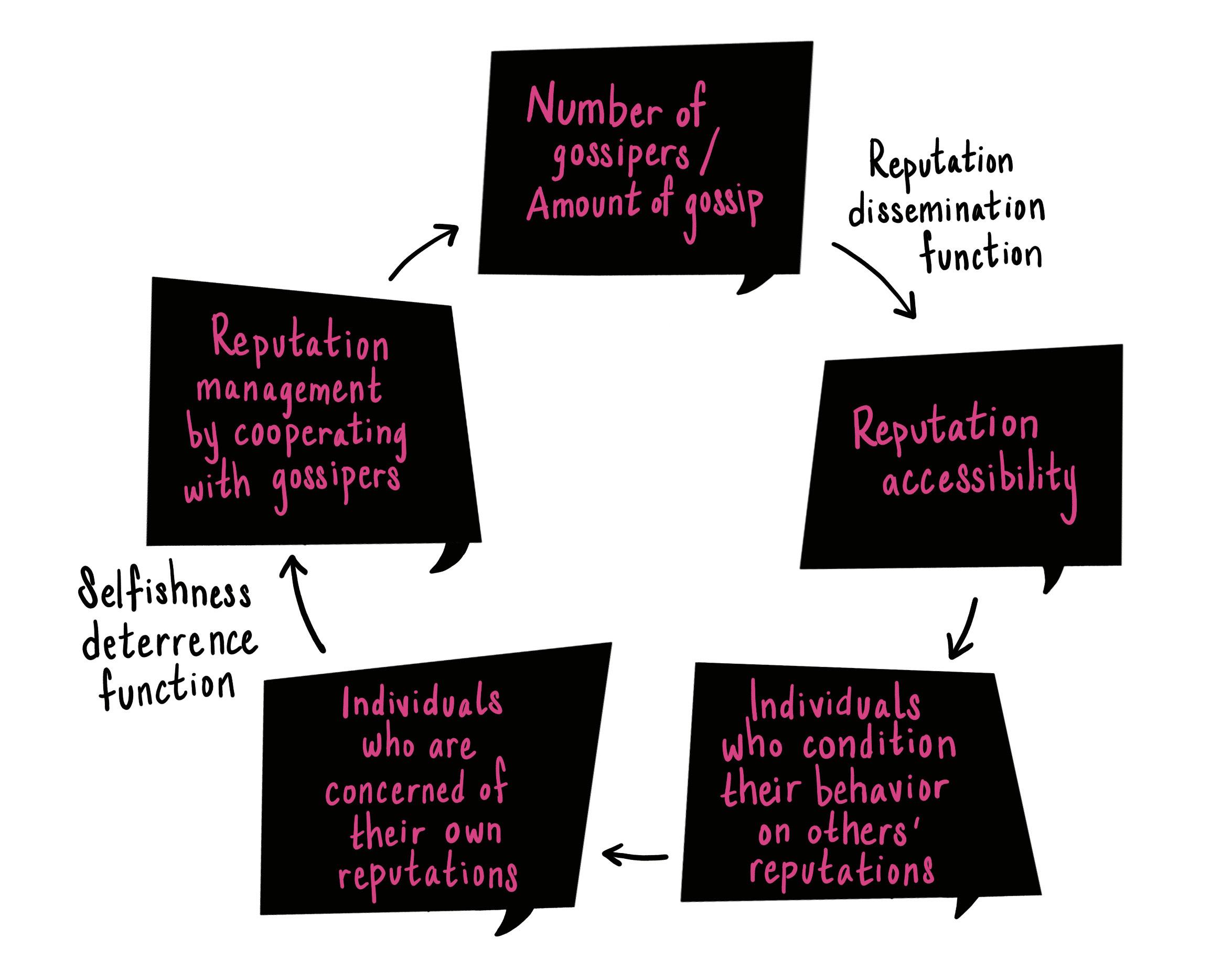

The researchers argued that people are more likely to cooperate in the presence of known gossipers because they want to protect their reputations and avoid becoming victims of rumors. For gossipers, receiving the cooperation of others can be a reward in itself.

“If you’re trying to be on your best behavior because other people know you’re gossiping, they’re more likely to cooperate with you on things,” Nau explains. did. “The fact that you gossip ends up benefiting you as a gossiper. Then other people will find it rewarding too, so they won’t gossip. Become.”

Thanks to their ability to influence the behavior of others and encourage cooperation, gossipers have an “evolutionary advantage” that perpetuates the gossip cycle and provides a beneficial service to their listeners. Pan also emphasized that although gossip has negative connotations, the information shared can be complementary. Regardless of its content, gossip has a useful function.

“Both positive and negative gossip are important because gossip plays an important role in sharing information about people’s reputations,” said Pan, now an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in Shenzhen. “When people have this information, cooperative people can find other good people to cooperate with, and this is actually beneficial to the group. So gossip isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It’s a positive It might be something.”

The fourth co-author is Dr. Vincent Hsiao ’18. ’24, a former student of Now and currently a researcher at the U.S. Naval Research Institute.

Nau acknowledged that the research does not cover the full range of human complexity and is not a replacement for behavioral research. However, his computer simulations may yield new theories that may prompt follow-up studies in humans.

“Humans are so complex that we can’t come up with a simulation that does everything humans do, and we don’t want to,” Nau says. “While this is an oversimplification and we cannot definitively say that this is the way people behave, it does provide insight. These can lead to scientific hypotheses that can be investigated through research involving human participants. It may be possible to connect.”

The researchers conducted a follow-up study to test one of the simulation’s predictions on human participants: the idea that gossip is effective in the absence of other ways to gather information about people’s reputations. I am thinking of moving forward with this.

“If you can formulate a hypothesis and then test the predictions of that model in human studies, that’s what makes this kind of thing useful,” Nau said.