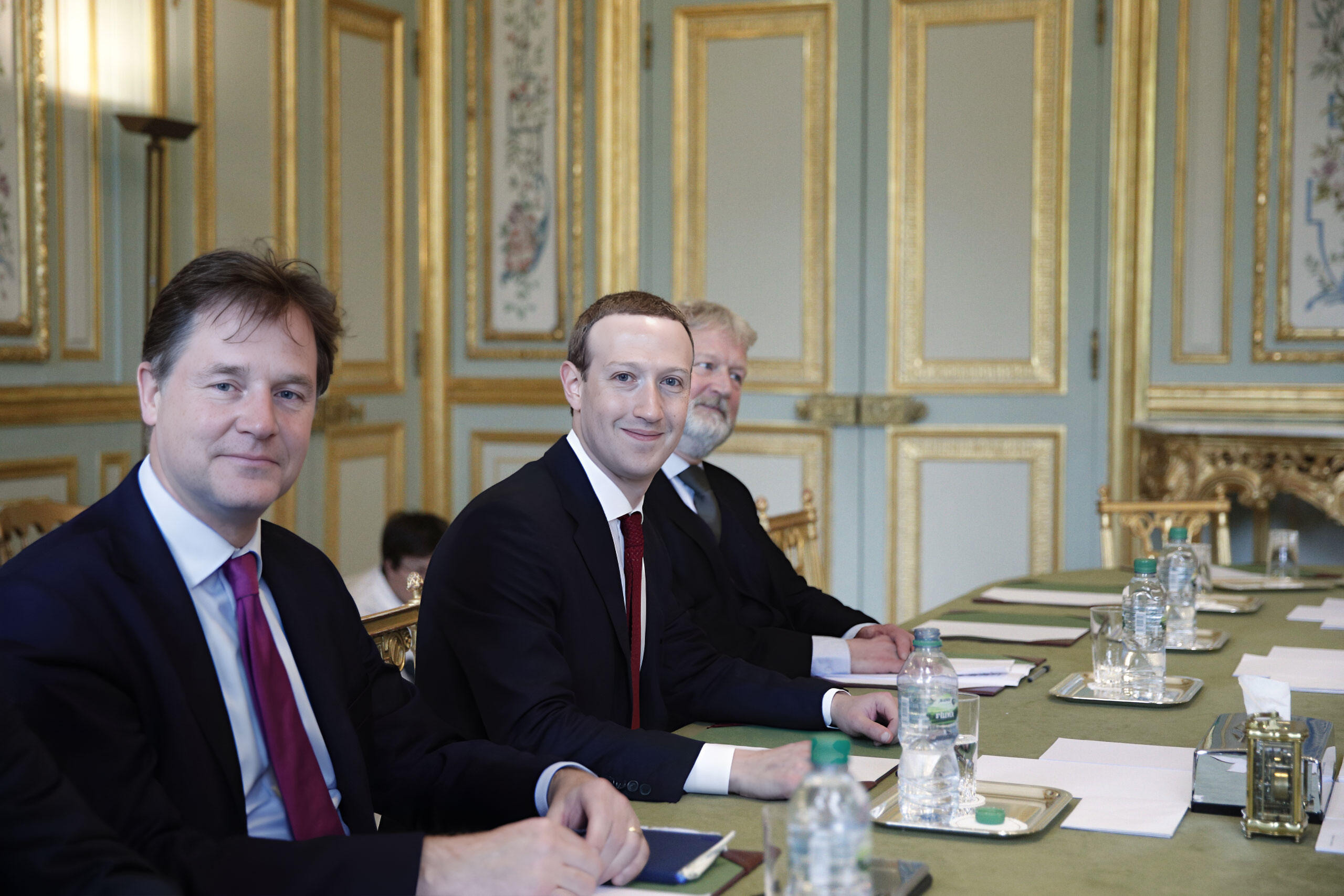

In six years, Nick Clegg has gone from political has-been to one of the most powerful executives at one of the world’s biggest tech firms: President of Global Affairs at Meta. As one of Mark Zuckerberg’s most trusted consiglieri, Clegg reportedly earns over $15 million a year and is tasked with dealing with the politics of its extraordinary global power and wealth. But is “the Foreign Secretary of Facebook” a constraining force on the media behemoth, or an enabling one?

Tom McTague, UnHerd’s Political Editor, has spent months investigating the darker side of Facebook. He has spoken to people in government, finance, tech and the police force, as well as friends of the former deputy prime minister to find out: is Nick Clegg whitewashing Facebook?

1. The reincarnation of Nick Clegg

2. The escape from California

3. Clegg battles Britain

4. The rise of Facebook fraud

5. How Clegg wields his superpower

1. The reincarnation of Nick Clegg

In July 2018, former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg was a mid-tier guest speaker at Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s inaugural “Democracy Summit” in Copenhagen. No longer an MP after being unceremoniously dumped from parliament in 2017 by a bar manager now in jail for fraud, Clegg was one of a number of former politicians who, having lost power, believed democracy was in trouble. Also appearing with the former Lib Dem leader were the two headliners that day: Joe Biden and Tony Blair.

The themes of that summit reflected the zeitgeist of the moment: the dangers of fake news and technology, particularly on social media platforms. For much of that year, Facebook had been under intense public scrutiny following revelations that people’s private data had been secretly collected and sold to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. The “Cambridge Analytica scandal” had seen Facebook’s owner, Mark Zuckerberg, dragged before Congress where he had given a hesitant and unconvincing performance in front of the world’s media, becoming a lightning rod for all the anxieties of the moment.

Rasmussen’s Democracy Summit was, then, another potential PR problem for Facebook. Yet, as one of the key sponsors, it also offered an opportunity to show how seriously it was now taking its responsibilities. Facebook’s Vice President of Global Policy Solutions at the time, Richard Allan, headed up the company’s delegation. Allan was the former Liberal Democrat MP for Sheffield Hallam who gave up his seat for Clegg in 2005, acted as his campaign manager, and was then granted a peerage by the Coalition in 2010. Also in attendance was Facebook’s former vice president, Joanna Shields, who had also been given a peerage under the Coalition, becoming a minister under David Cameron and then Theresa May’s “special representative on internet crime and harms”.

So, while Clegg was a rather bruised former politician, he remained a very well-connected one. When the conference ended, he did not even have to sort his own travel home: Blair offered him a lift back to London in his private jet. Here was a taste of the gilded life he might aspire to in his political retirement, the life of a former politician no longer constrained by democracy.

But Clegg, thanks to that summit, has taken quite a different path from almost any previous British politician. He had never been that interested in technology, according to those who know him. But as Allan told me recently: “The event was one of those moments which helped Nick understand how politically significant all this was.” Within a few months, Clegg had joined Facebook, and relocated to the US. He has since risen to become one of the most senior executives at its parent group, Meta — no longer merely deputy prime minister of the UK, but, according to those I spoke to in Whitehall, effectively “Foreign Secretary of Facebook”.

Clegg’s importance at Meta was revealed last year when he negotiated both his return to London and promotion to “President of Global Affairs”; a position which reportedly earns him upwards of $15 million a year. Six years after his career low-point, Clegg is now Zuckerberg’s trusted consigliere, the political representative for a $1 trillion corporate behemoth. He is the man paid to ensure Zuckerberg is not exposed to the sort of political scandal that dragged his name through the mud in 2018.

In short, Clegg has it all: not only the kind of power, wealth and settled family life back in London that few former politicians could ever dream of, but also his reputation repaired and even enhanced. No longer a humiliated political loser, he is now the man tasked with making the world’s most important media company more socially responsible and saving democracy from the populists in the process.

While Clegg remains relatively guarded about this new life — he would not agree to be interviewed for this piece — his wife Miriam González Durántez’s Instagram page is like a show reel for what it all looks like. There he is with his wife one moment, hiking in Africa, smiling for the camera, soaked in the mists of Victoria Falls; then in the United States; and then back in England walking in the countryside. “Happy birthday Nick Clegg!” Miriam writes below one image of the pair of them. “Life with you is an incredible journey.”

“Y’all shooting Clarkson’s farm?” one of Miriam’s friends jokes in reply to her birthday post, the rolling English countryside clearly visible behind them. “I’ve watched two episodes and I’m hooked!” Miriam replies. “At least it’s anti-Brexit!!” For Miriam the nature of her husband’s departure from politics — and what came soon after — remains a source of bitterness. Under a news story that she posted on her Instagram feed about David Cameron returning to frontline politics as foreign secretary, she remarks, “Clearly getting bored at home,” before adding, acidly: “And yet home is where he truly belongs.” When a friend replies, “I thought it was George O you really hated”, Miriam posts a laughing emoji. When another adds, “what a joke of a man”, Miriam responds with a heart.

But is her husband really so different from Cameron? “The only difference,” one senior government minister said to me, “is that David is back in government trying to launder his reputation — whereas Nick is selling his to launder somebody else’s.”

This is central to any consideration of Clegg’s new life: is he really the liberal constraining influence on Meta that his defenders claim, the man making Facebook that little bit more responsible for the good of us all? Or is he, actually, an enabling force, giving a veneer of respectability to a company that is so big it has moved beyond the control of mere national governments and remains just as socially irresponsible as ever? For, according to those I have spoken to in the British Government and law enforcement over the past few months, Meta’s influence is not becoming more benign under Clegg — quite the opposite.

I was told by a senior minister that, in the UK today, 10% of all crime happens on a Meta platform. “That’s not online crime,” he said, “but all crime.” And it is getting worse. Not only has online fraud exploded on Facebook marketplace, but child exploitation is being made easier by Meta’s decision to ignore pleas from law enforcement agencies and government ministers not to roll out “end-to-end encryption” across its platforms, in effect making it much easier for paedophiles to groom and abuse children without anyone knowing. “They are responsible for an awful lot of harm in this country,” another minister told me.

And yet what is being done about it? According to those I spoke to in government, Britain has become a global soft touch for online criminals, attracted to the country by the ease of operating in English, our economic openness, speed of online payments — and, crucially, the utter inability of the state to do anything about it.

2. The escape from California

Clegg’s time in California was important, say those who know him, because it allowed him to get close to Facebook’s “C-suite” executives — in particular, Zuckerberg himself. For much of this time, his boss was Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s all-powerful number two. When she stepped down in the summer of 2022, Zuckerberg relied instead on a team of lieutenants, one of whom was Clegg. With this direct relationship established, Clegg felt secure enough to move back to Britain.

According to Meta, he only occasionally interacts directly with the British Government — his job is now too important for that. “He spends most of his life on a plane,” I was told. In January, he was in Switzerland for meetings about AI; in December, in Brussels to talk to the EU; in October, Greece for another summit about democracy; and over the summer, India, where he was greeted like a visiting head of state.

Clegg’s job at Meta is to set overall strategy for dealing with the world’s most powerful regulators, oversee Meta’s own governance strategy and manage the politics that inevitably come with its extraordinary global influence and wealth. In total, there are now 3 billion “monthly active users” on Facebook, 2 billion on WhatsApp and 1 billion on Instagram. If Meta is now the size of a country, Clegg is both its cabinet secretary and its chief diplomat.

As such, Meta is not just another social media company, but a monster of global proportions: an international news platform, publisher, marketplace and advertising giant all rolled into one, used not just by ordinary people, but also by criminal gangs, sexual predators, authoritarian governments and terrorists. Indeed, one of Meta’s own lines of defence is that its very size is the reason why so much crime happens on its platforms.

Clegg’s defenders argue that, since joining Meta in 2018, he has moved the company away from its more libertarian instincts towards a more “mature, sensible place”, where it apparently acts more proactively in addressing public concerns about its role in things such as deep fakes, sexual exploitation and fraud. He has, they say, been instrumental in making Meta less hostile to regulation while creating new layers of governance for the platforms. He created the independent “Oversight Board” which now makes decisions on free speech and content on Facebook and Instagram, and which has been filled with unimpeachably liberal bigwigs such as the former Danish prime minister, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, who lives in London, and the former editor of The Guardian, Alan Rusbridger. These are Clegg’s people.

The Oversight Board has certainly helped to reduce the kind of political controversy over Facebook censorship which dogged the company during Clegg’s early years, when Donald Trump was removed from the site. Yet this innovation also points to the question about Clegg’s influence. “I mean, come on,” said one of the senior UK government figures I spoke to. “Does anyone really believe the ethics board is anything more than a rubber stamp for the same old West Coast liberal politics the company has always had?” To Clegg’s critics, in other words, it’s all just window dressing for the same corporate interest.

Over the past months, I have spoken to more than a dozen figures in government, finance, tech and police, as well as those who know Clegg personally, to try to understand how much he has really managed to achieve at Meta. Those who have come across him at work describe the same figure who burst into the public consciousness in 2010: fluent, charming, persuasive, normal.

One British minister who had dealt with Clegg in government told me he was the same as ever, only now with the air of corporate power behind him. Another MP said he was “charming but defensive” when representing Meta. Another who met him in California told me that while he was thriving professionally in the US, he was clearly out of place in Silicon Valley’s deracinated suburbia, too far removed from the Victorian warmth of south-west London where the family had made their home and to which they have now returned — albeit to a new £8 million home in Chiswick.

Clegg and his wife disliked the scale of urban poverty in California that sat alongside the kind of extraordinary tech wealth that they were benefiting from. Both felt that their time in the US had confirmed how European they were and, while they might hate Brexit and the Conservative Government, London was nevertheless home. While they were there, Miriam lectured on international trade policy at Stanford University, but she has her own political ambitions in Europe. Since returning, she has created a new political movement — or “nascent political party” as one friend described it — called España Mejor, or “Better Spain”.

It was always the pair’s Europeanness that made Clegg such an attractive prospect for Zuckerberg. He is, explains one friend, fluent in European in a way Zuckerberg is not.

3. Clegg battles Britain

“The tech industry needs to work together to fight predatory adults online,” Clegg tweeted in November. “That’s why Meta is a founding member of the Tech Coalition’s new Lantern programme, which will allow companies to share signals about predatory behaviour & take action on their respective platforms.”

A month later, Meta announced that it was rolling out end-to-end encryption for all personal chats and calls on Messenger and Facebook, meaning, as it boasted at the time, “the content of your messages and calls with friends and family are protected from the moment they leave your device to the moment they reach the receiver’s device”. As a result, “nobody, including Meta, can see what’s sent or said”.

For years the British Government had been lobbying Meta not to go through with this plan. Today, Britain receives around 800 referrals every month from the US-based National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), an organisation which trawls the internet looking for evidence of child exploitation. When NCMEC finds evidence of wrongdoing it passes it on to national crime agencies around the world who then go to arrest the abusers operating in their country. As a result of these 800 referrals, around 1,200 children are protected from predatory adults every month. By rolling out end-to-end encryption, the UK Government believes this number will collapse overnight.

In 2022, there were around 32 million reports of online child sexual exploitation made to NCMEC — 21 million of which came from Meta. When I put this to Meta, they pointed to comments by the NCMEC executive John Shehan, who recently praised the company for going “above and beyond” in their search for online child sexual exploitation while other companies did not, and there seems to be some truth in this. While Facebook referred 21 million reports to NCMEC in 2022, Google reported 2.2 million, TikTok 290,000 and X just under 100,000. Apple reported just 234. And yet, by rolling out end-to-end encryption, Meta has, in effect, wilfully blinded itself to at least some of what is happening on its platforms, even if it insists there is still much they can do to combat child sexual exploitation.

A Meta spokesman told me: “We don’t think people want us reading their private messages so have spent the last five years developing robust safety measures to prevent and combat abuse while maintaining online security.” Here is classic Cleggite third-wayism. Meta points to things such as enforcing age limits, using technology to scour for suspicious behaviour and stopping adults contacting children they don’t know. The company says, for instance, that it can block anyone over 19 from starting a direct conversation on Instagram with children they don’t follow. Meta also says it has developed technology to identify “suspicious adults” — for example, if they’ve recently been reported or blocked by a teen — which would prevent them from finding, following and interacting with teen accounts. But if adults are this suspect why aren’t they just thrown off Facebook altogether?

Another safety feature Meta boasts about are the “safety notices” it sends to teenagers if they are talking to suspicious adults. In just one month last year, 85 million users apparently saw such safety notices. And yet, as a parent, it is hard to feel reassured by such statistics rather than simply terrified at the scale of potential abuse. Other defenders of Meta argue that end-to-end encryption does not disempower the police. Encrypting messages does not stop undercover police entering WhatsApp groups or seizing mobile phones. Meta insists that overall, even with end-to-end encryption, it expects to continue providing more reports of potential child sexual exploitation than other social media companies. We shall see.

The British Government, at least, is far from convinced. In the autumn of 2022, the then home secretary, Suella Braverman, held a video call with Clegg about the issue. In this meeting, Clegg claimed Meta was being unfairly targeted because it was making the majority of referrals to NCMEC. From the British Government’s perspective, though, this was exactly the point — it is making so many referrals because there is so much abuse happening, which will now be harder to do anything about. The discussion ultimately ended without agreement: the UK Government insisted that it was possible to protect privacy and child safety by developing new technology to sit alongside end-to-end encryption. Clegg insisted that it was not.

It looks, to those in government, like Clegg has absorbed the prevailing libertarian orthodoxy of California: an orthodoxy which places privacy above all else. In Silicon Valley, there is an arms race to offer customers total privacy in their private communications, no matter the cost. For the British Government, the cost of such unbreakable privacy is simply too high. Instead, it believes technological solutions are possible that allow social media companies to scan for illegal material on encrypted platforms, while also maintaining privacy. “We know it’s possible, because GCHQ says it is,” one government figure told me. The British state, in other words, had developed the technology itself. Meta says most experts disagree.

After Braverman and Clegg’s discussion in 2022, the pair did not meet until 2023. In the meantime Braverman ordered the Home Office to produce a public campaign directed against Meta’s planned roll out of end-to-end encryption which would target Zuckerberg directly, pleading with him “as a father” to change course. The plan, in effect, was to launch a coordinated government attack on the Facebook founder to shame him into action by turning public opinion against him. But, then, Rishi Sunak ordered Braverman to pull the campaign.

Why would he do this? On this point there remains a fierce dispute between ministers. Some see something nefarious — Sunak eyeing a future career like Clegg’s — others the power of the Treasury, others mere political tactics or Sunak’s weakness. What is certainly true is that there was a campaign and then there was not.

It was also at this time that the Government began trying to reassure Meta about the measures contained within its then-controversial Online Safety Bill, which was making its way through parliament. Under the Bill’s provisions, social media companies such as Meta would be responsible for the content on their platforms and would have a new duty to “identify, mitigate and manage the risks of harm” from illegal content and “activity that is harmful to children”. The legislation also gave the powers to enforce this to Ofcom, the media regulator. Ofcom, the act states, could order Meta to use “accredited technology” to look for and take down child sexual abuse material on its platforms, and also to levy fines up to 10% of a company’s global annual revenue.

Facing this threat, in March 2023, Meta warned it would pull WhatsApp from the UK if the proposed measures in the Bill were not removed. But, then, in September — just as the row between Braverman and Clegg was reaching its climax — the Government moved to reassure Meta and the other social media companies that Ofcom would only be able to force them to scan WhatsApp, Messenger and Facebook for illegal content if that was “technically feasible”, which Meta insists it is not. In the end, the Bill received royal assent in October without the changes once demanded by Meta, but with responsibility for dealing with the problem kicked over to Ofcom.

No one knows how Ofcom will use its new powers — or how powerful the new law will actually be. One thing we do know is that since the passage of the Online Safety Act in September, Meta has not only not pulled WhatsApp from the UK but has felt free to push ahead with the roll out of end-to-end encryption across its other services. “The truth is we’re too scared and timid,” said one government figure involved at the time. “As ever.”

When I opened my phone this weekend, I noticed a little message on WhatsApp. “We’re updating our Terms of Service and making relevant changes to our Privacy Policies for UK users, effective 11 April 2024,” the note read. The changes are necessary, it went on, “to reflect that the minimum age to use WhatsApp in the UK will be changed from 16 to 13“.

4. The rise of Facebook fraud

Alongside the Online Safety Act, the principal challenge for Meta over the past year has been the growing anger over the explosion of fraud on its platforms, particularly Facebook. According to the Government, fraud now accounts for 40% of all crime in England and Wales, 70% of which comes from abroad with as much as 80% happening online — the vast majority on social media. In recent evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee, the TSB’s Financial Crime Prevention Director, Paul Davis, said 80% of the fraud they saw originated on social media, before adding: “Let’s not walk past the fact that when I say ‘social media’, the majority of them start from the channels owned by one company in particular, which is Meta.” Baroness Nicky Morgan, chair of the House of Lords Fraud Act Committee, told Meta that she had received written evidence from high-street banks that in one three month period alone, 70% of all cases of investment fraud started on Facebook or Instagram, either through adverts or victims being directly messaged.

The police are seeing the use of social media and “encrypted messaging services” like WhatsApp by criminals “increasing throughout all aspects of fraud”.

While Clegg sets Meta’s overall political strategy, he tends to defer the job of defending Meta’s interests in the UK to the team he has assembled in London, most of whom also used to work in Whitehall.

Meta’s director of public policy in London is Chris Yiu, a former No. 10 adviser and Treasury official who went on to become one of the most influential figures at the Tony Blair Institute (TBI). Yiu is credited within the TBI as being the man who convinced Blair of the revolutionary potential of technology, setting him off on his journey towards Oracle’s Larry Ellison, who now funds most of his work calling for much greater use of technology by government. Yiu remains close to Blair, becoming one of the TBI’s board members in 2022, a position he still holds, alongside his job at Meta.

Alongside Yiu, there’s Rebecca Stimson, who was in the Cabinet Office during the Coalition as a senior EU policy advisor to Cameron. Then there’s Richard Earley, Meta’s “Head of UK Content Regulation Policy”, who also worked in the Cabinet Office with Clegg during the Coalition, and Philip Milton, who does much of the direct interaction with the Government on the issue of online fraud. Before joining Meta, Milton previously worked at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, “with responsibility for e-Privacy, Data Protection and Net Neutrality policy”, and before that at the Serious Fraud Office. For Meta, Whitehall is less a revolving door than a one-stop shop from which to poach its lobbyists.

When Milton appeared before the House of Lords in 2022, he claimed that dealing with online fraud was Meta’s “number one priority”. “Without our users, our platforms cease to exist, it is as simple as that,” he said. “Even if they do not necessarily fall victim to fraud, the very presence of it degrades users’ experience, and it makes it an unattractive place for advertisers to use as well.”

Yet, according to those I spoke to within the British Government, Facebook has been the slowest and least effective of all the Big Tech companies in reducing fraud on its platforms. When Google changed its algorithm so that it would only take adverts from investment products regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, the amount of online fraud coming from the site collapsed to almost zero. Meta, in contrast, dragged its feet and is only now doing something similar.

Far from being motivated to act, one senior government insider told me, Meta’s business model and sheer size meant it was, in fact, incentivised to move much more slowly than other companies. “If you are eBay or Gumtree, then fraud on your marketplace is a real problem because it’s your bread and butter,” they explained. “For Meta, they are ultimately an advertising company, so eyeballs on site is what they need, so the incentives are completely different.”

Meta’s principle strategy was to avoid any new legal obligations imposed upon it to deal with the fraud — or, more specifically, any new legal liabilities to recompense those who had been defrauded through its sites.

Today, pressure for the Government to do something is not just coming from consumers who have been ripped off online, but from Britain’s powerful banking sector, which has become incensed at the amount of money it is having to pay out in compensation to those defrauded on social media. The issue has become more acute because of a new regulatory regime coming into force in October this year, which will mean almost everyone who is defrauded online will be entitled to a full reimbursement. At the moment, most banks voluntarily reimburse their customers, covering around two-thirds of all fraud cases. Under the Government’s new rules, however, almost all claims up to £415,000 will be covered — some 99% of all cases — with the cost of the compensation split 50/50 between the bank of the fraud victim and the bank of the fraud thief. The social media platform on which the fraud took place will not have to pay a penny.

To deal with this discrepancy, there has been a growing push inside the Government for tighter rules on tech companies — Meta in particular — to force them to clamp down on the fraud on their sites. The Government has had two “anti-fraud champions” over the past year or so — Anthony Browne and then Simon Fell. Both have publicly backed calls for the burden of compensation to be shared between the banks and social media companies. For Meta, this is not just a financial irritation but also a potential legal principle that could become a new gold standard across the world.

Before the party conference season last year, formal proposals went into No. 10 that included a recommendation that the Government look again at “burden-sharing” as part of a new Online Fraud Charter. According to one minister, two of the Prime Minister’s closest advisers — James Nation, deputy head of the policy unit, and Will Tanner, deputy chief of staff — were demanding the Government “push hard in this space”.

And yet, when the Charter was eventually published in November, there was no mention of it. Instead, the Charter was a kind of voluntary compact between the Government and tech firms to do more to deal with fraud, with a review to take place in six months to see how they are getting on. The tech companies — and Meta — had dodged a bullet. “The lack of anything in the Fraud Strategy caused quite a stir from the financial services sector,” the minister told me.

Even getting Meta to accept some responsibility for the content on its platforms took an enormous effort and the direct lobbying of Clegg to get it over the line. “It is the first time they have ever accepted responsibility for what is on their platforms,” one insider said, “so it’s a big mental boundary that they’ve crossed, which we shouldn’t overlook.”

In the run-up to this turning point last year, Clegg spoke to Bob Wigley, Chair of UK Finance, after which he ordered a number of his juniors to engage directly with Anthony Browne, the Government’s then anti-fraud champion. Following one such meeting, Browne wrote to Clegg directly to say he was “very pleased with the new identification measures that Meta is taking to combat fraud on your platforms” and that he was “confident they will have a real impact, and benefit millions of your users in the UK”. He concluded: “Thank you for your constructive approach and taking the issue with the seriousness it deserves.”

Meta says that while the Government has not made it financially liable for site fraud, the Online Safety Act does list fraud among the harms social media companies have a duty to combat — with fines of up to 10% of its global turnover if it does not. Meta also insists that the commitments it has made in the Online Fraud Charter are significant. For instance, it will soon be rolling out “increased verification” on Facebook Marketplace, introducing warning messages to encourage users never to pay for an item without seeing it first. But why has it taken so long to get here? And if it takes the threat of government action to do it, why aren’t we demanding more laws with more bite all over again?

According to a number of insiders involved in the process, the real brake on imposing burden sharing was the Treasury and Jeremy Hunt in particular. “It was a combination of the two of them,” said one government figure. The Treasury does not want to impose financial burdens that make Britain less attractive for inward investment, particularly from tech companies. A second figure confirmed that the reason the social companies had escaped without any new liabilities for the fraud was because of “competitiveness issues”. A third said: “As ever, the Treasury is reluctant to choke off any potential UK investors with what they see as punitive measures.”

For Hunt, personally, one of his central objectives as Chancellor is to make London and “the triangle” with Oxford and Cambridge “the Silicon Valley of Europe”. In his Autumn Statement, he boasted that Britain already had the “third largest technology sector in the world, double the size of Germany and three times the size of France”, but wanted to go further. Meta has already invested heavily in London, with a big new campus at King’s Cross, one on Rathbone Place and another on Warren Street. It is from Warren Street in particular that Clegg is able to “hot desk” whenever he goes into the office. Hunt’s vision has also been embraced by Sunak, the tech bro with a place and a former career in California.

And so, what is the result? Next month the UK Government is hosting the first ever Global Fraud Summit in London, attended by interior ministers and figures from Interpol, the EU Commission and the UN. And who has been asked to give a presentation on how to share intelligence? Meta.

5. How Clegg wields his superpower

If Nick Clegg has a superpower, it is surely the illusion of normality. He is the public schoolboy in an M&S pullover helping to run one of the world’s great hegemons. It was this ordinariness that once made him politically popular, but which also contributed to the ferocity of the backlash when it came. The country had briefly fallen in love with this new Blair, only for him to let them down, just like the old one.

His skill as a politician was to always adopt the demeanour of the most sensible person in the room, neither irresponsibly libertarian nor hysterically conservative. It is the same trick he plays today. When Clegg bemoans those fixated on “speculative future risks about AI models that currently do not exist”, this may sound like third-way centrism, but it is also no coincidence that this reflects Meta’s corporate interest in maintaining a light-touch regulatory system for as long as possible.

Again and again, Clegg has adopted the same strategy: shepherding Meta into a place where it can say it is already regulating itself — and so does not need sweeping new regulations imposed upon it. But all the while, things are getting worse online, not better, and Clegg is the man ultimately responsible for Meta’s overall political strategy — a strategy which, I was told by four separate figures from within the UK Government, was self-interested, slow and resistant to any real democratic challenge, reticent to do anything which affects its corporate bottom line or sets damaging regulatory precedents which could be adopted elsewhere.

“There’s no question in my mind that he is an enabler,” one former colleague at Meta told me. “The only question is whether he realises it or not.”

Far from a burnt-out politician, Clegg is now a private citizen with extraordinary power and responsibility, paid a fortune to promote the interests of a company whose policies affect the lives of billions. If the US Congress can hold Zuckerberg to account, why isn’t the British Parliament doing the same to Clegg?

But it is also true that when trying to piece together his influence, the British Government has also shown itself to be as full of contradictions as Meta. During my conversations I heard how unimportant Clegg was to Zuckerberg, a figure to be held in contempt for selling his reputation for money. But I was also told how instrumental he was in dragging Meta over the line to sign the Online Fraud Charter. Meanwhile, some ministers boasted about how the Government had refused to give in to threats from Meta, while others lamented how ineffective they had been. Some blamed the Treasury, others No. 10 and others still a general mindset of British state weakness, made worse by splits within the Cabinet between security-conscious departments such as the Home Office and rivals such as the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

For all this pointless squabbling, a simple reality remains: Clegg might be an influential figure in a giant corporation, but the British Government is responsible for the laws which apply in Britain. If Britain is a soft touch, that is the Government’s fault. The question of whether he is a restrainer or an enabler is, then, moot: he is, inevitably, both. The real question is one of power. Clegg and the British Government have it. And we should be angrier with both for how they use it.