Ife Adebara is on a mission to make technology accessible to everyone on the African continent. This is about making their languages available to all people on the African continent in the technology they use.

“People who speak minority languages have to put their language aside to make technology available in English, for example,” said Adebala, a programmer and academic at the University of British Columbia’s Department of Linguistics. Ta.

“Over time, their language use will start to decline, which could have long-term consequences of a language crisis…We need to mitigate that.”

Adebala said AI technology is advancing rapidly but is leaving behind people who speak languages other than English.

Her project, called Africa-Centered Natural Language Processing, works to create awareness, tools, and programs accessible to ordinary people who speak African languages, including Swahili and Zulu.

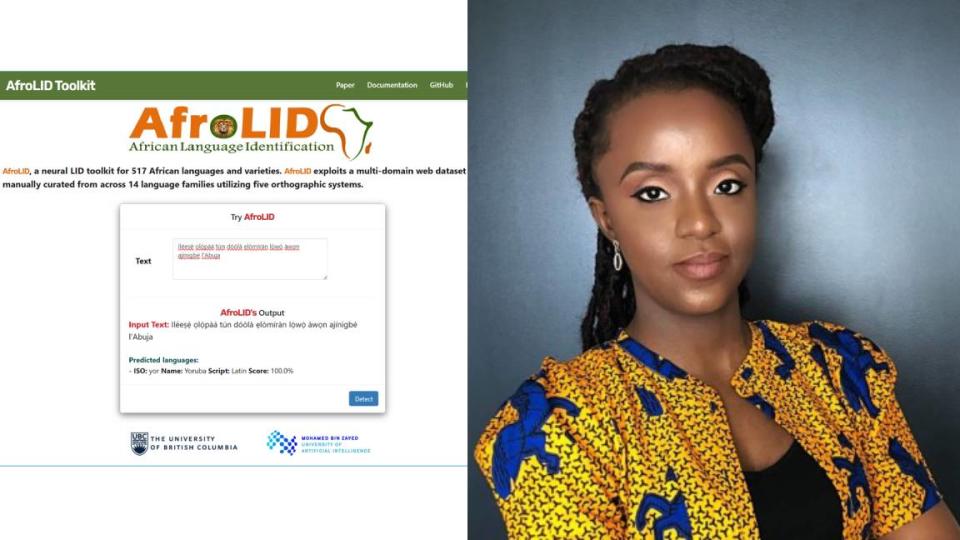

So far, she said, the team has released two language identification programs online: SERENGETI and AfroLID.

Prior to her interview, Initial versionAdebala spoke with CBC’s Ali Pitarug to talk more about his work and the need to make technology inclusive.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What is the AI and African Languages Initiative?

The idea is to provide African people with technology in their indigenous languages.

This involves developing these assets, building and deploying artificial intelligence models to African people, and enabling them to interact with the technology in the language they are most comfortable with (usually an indigenous language). It is included.

What language are you working on?

There are over 2,000 languages in Africa. Currently, he works on about 517 languages spoken in 50 out of 54 countries in Africa.

That number is growing as more languages are added to the list I’m working on. The goal is to be able to use as many languages as possible within the African continent.

These languages are often called low-resource languages. Can you tell us more about that and the challenges associated with it?

Low-resource languages are languages that don’t have adequate data to build classical language models for AI.

Therefore, the challenge with this type of language is that it typically performs lower than resource-rich languages such as English, French, and other Indo-European languages.

One approach I’ve used to alleviate this challenge is to group many languages into the same model. This way, the model learns from multiple languages, the dataset is larger than before, and the performance is slightly better.

However, this problem still needs to be solved as achieving near-human accuracy requires more data to achieve it.

Why is it important that African languages are not left behind in these technological developments?

This is important for two reasons. First, more than a billion people in Africa, about 17 percent of the world’s population, are excluded from the global conversation in their indigenous languages.

They don’t listen to others and we don’t listen to them.

Another is that the grammatical features of many African languages are highly diverse and, in some cases, unique to the African continent.

If you build your language technology to exclude African languages, your models and technology will not learn certain language features. This is also not good. This is because it lacks generality across the variety of grammatical features present in human languages.

What do you hope this project will accomplish overall?

I hope this technology becomes available and accessible to the average African. This will definitely have a long-term impact on education.

Users can access information on the web in their own language that has been translated into their language or translated from another language. We see people being able to access health information in their own language, use Google Maps, and more.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians, from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community, check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

(CBC)